Some observations on state repression

international |

rights, freedoms and repression |

feature

international |

rights, freedoms and repression |

feature  Tuesday April 27, 2010 19:14

Tuesday April 27, 2010 19:14 by Gerry Nobody

by Gerry Nobody

Not really sure where to post this—just got thinking about repression and state power etc. and thought I would share some observations on the subject with whoever’s interested. Yes, it ended up being more of an essay than a post but what the hell—feels good to get it off my chest.

Related Links: Court rules Garda Supt. M. Larkin responsible for Violation of the Rights of Shell to Sea activists. http://www.indymedia.ie/article/96213

Shell ignores the law but gets campaigners jailed http://www.indymedia.ie/article/96137

Erris Rally of Solidarity with 'the Chief' Pat O'Donnell. http://www.indymedia.ie/article/95932

Eoin O'Leidhin - Interview http://www.indymedia.ie/article/95907

Another Shell to Sea Campaigner Imprisoned. http://www.indymedia.ie/article/95900

Shell retreats as solidarity with Pat O'Donnell continues http://www.indymedia.ie/article/95880

Court Report from Mayo http://www.indymedia.ie/article/95776

Shell Corrib Gas - Who are the real Thugs & Bullies? http://www.indymedia.ie/article/95795

Massive Works Planned in Erris Waters while "The Chief" is in Jail http://www.indymedia.ie/article/95785

Community Power at the Rossport Solidarity Camp http://www.indymedia.ie/article/95731

Bolivian Peasant leader comes to Ireland to demand IRMS investigation http://www.indymedia.ie/article/94855

Corrib Pipeline (Bord Pleanala Decision) http://www.indymedia.ie/article/94649

Orwellian Ireland http://www.indymedia.ie/article/70223

Given the events at Rossport over the last few years, the issue of how states like Ireland suppress political dissent has been on many people's minds for some time I think. I suppose I should clarify what I mean by ‘states like Ireland’ as opposed to a police state like East Germany or a military dictatorship like Myanmar. I would plumb for the term ‘parliamentary democracy’ (as opposed to a participatory democracy), in which parliament, although formally chosen by the people every five years (this is about the extent of our participation), is by and large controlled by the interests of big capital.

What started me thinking about the issue of repression in particular was something I witnessed here in Sweden, where I live. I was at one of these meetings that foreigners moving to Sweden have to attend—a sort of Introduction to Sweden course for immigrants, designed to facilitate your integration into the country I suppose. Most of the other people in the room besides me were asylum-seekers from Iraq, Iran, Palestine or Afghanistan and the teacher was talking about the political system in Sweden. He made brief mention in passing of some small political groups, such as Communists and Islamic fundamentalists, who did not accept the legitimacy of parliamentary democracy in its current form. I suppose he thought he was calming the fears of those present (many of them were probably victims of political instability in their own countries) by telling them not to worry about such people, as the secret police kept a close eye on their activities to make sure they never posed a threat to public order.

The irony of calming these people’s fears—by telling them that the secret police were keeping an eye on things—did not seem to strike the man. Sweden would not strike most of us as a particularly oppressive state. In fact it is probably one of the countries with the best balance between civil liberties and state intervention I know of. Another thing to note is at least they openly admit spying on certain defined political groups. The Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz—Germany’s domestic intelligence agency, is similarly upfront about spying on the fourth largest political party in the country Die Linke (The Left) because it falls into the category of extremist. If only all parliamentary democracies were as transparent about which groups were being spied on for political reasons, we would at least know where we stand.

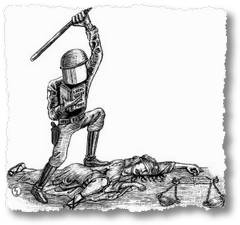

Instead, what we often find is that political repression is carried out under the guise of preserving public order. History is full of examples of this, and of its consequences.

Thinking of Germany, one of the most dramatic examples that springs to mind is the student movement in the sixties. At one stage its aim was to achieve radical change in German society by peaceful means. The fact that it was large and effective enough to threaten the status-quo is attested to by the ferocity of the attacks against it by the police and capitalist media outlets. The suppression of the movement is best exemplified by the attempt to assassinate one of its chief spokesmen, Rudi Dutschke, in 1968. Faced with a system unresponsive and downright hostile to their attempts at change, many radicals chose to take their struggle underground. The Baader-Meinhof group can be seen as emerging from this desperate state of affairs. There is a scene in the Baader Meinhof Complex film where a brain-damaged Dutschke turns up at the funeral of one of the Baader-Meinhof members who has died on hunger strike years later. There is a very poignant sense of what might have been had people like Dutscke not been sidelined by the state’s suppression of peaceful protest.

Of course we don’t need to look so far afield for examples of the state suppressing legitimate political activity. Legislation in Britain, such as the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005 (note 1) and the amended Protection from Harassment Act 1997 (note 2) has effectively criminalised whole areas of peaceful political activism, or at least made its legality enough of a grey area so as to deter most people from getting involved. In Austria, Section 278a of the Penal Code (ostensibly intended to combat organized crime) is being used to persecute the animal rights movement which has been a little too successful for comfort (note 3). And of course, in Ireland the state’s use of the Guards, private security firms and the judiciary itself against the Shell to Sea campaign in recent years is in a similar vein. The bitterness is palpable amongst many who have followed these events. In some cases there is anger; sometimes, a frustrated sense of helplessness. I think that historically, when the state closes down all avenues of peaceful and constitutional opposition, this has had a twofold effect.

Firstly, it tends to drive a (usually small) number of people into violence. Deprived of any means of exercising their right to challenge state and capital legally, some people will not choose to simply throw in the towel but will instead be driven underground. The key here is that their numbers are usually (with certain significant exceptions of course) small enough for the state’s security forces to contain and isolate from the rest of the population. They may cause a great deal of damage to property and even loss of life, but organizations like Baader-Meinhof were never a threat to the West German state. Even the Provos, I would argue, had been pretty much contained in this sense by the late eighties. Although they might have posed a real threat to British control over the north for a time in the seventies, the Thatcher government had little-enough regard for the lives of its own citizens to be prepared to live with the security threat of the IRA for an indefinite period of time, although even the iron lady herself must have had moments of doubt, at Brighton in 1984 for example. States that employ this strategy are therefore content to trigger this kind of violent dissent, if it can be reduced to the proportions of a security threat. The Guards/Police/Stasi will ‘look after it,’ and even sacrifice their lives occasionally for the maintenance of this status quo.

It is worth their while because of the benefits they reap from the second reaction of people to the suppression of peaceful resistance, and I believe this is the reaction of the majority of people when faced with such repression. They simply give up or don’t get involved in the first place. It is these people who are the real object of repression. The powers-that-be fear most the normally-quiescent majority who will, given the choice, opt for a quiet life unless their rights are impinged upon to an unbearable extent. We can call them apathetic if we wish, but there is a reason for this apathy and the object of all this repression is to make sure that it stays that way. The powerful see what the people power achieved in Eastern Europe in 1989 for example, and they are terrified that it could happen again. For all their talk of trying to encourage more of us to vote and get engaged in the political process, I believe this is the last thing they want.

1 under a provision of which Maya Evans, a vegan cook, was arrested in 2005 for reading out the names of casualties in Iraq within a kilometer of parliament. Sections of this act were also specifically tailored to define as threatening and illegal behaviour, almost any conceivable protest against animal-testing laboratories such as HLS

2 see http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2009/feb/05/ant...ntral

3 see http://www.shameonaustria.org/en/index.php