Mayo no events posted in last week

A bird's eye view of the vineyard

Alternative Copy of thesaker.is site is available Thu May 25, 2023 14:38 | Ice-Saker-V6bKu3nz Alternative Copy of thesaker.is site is available Thu May 25, 2023 14:38 | Ice-Saker-V6bKu3nz

Alternative site: https://thesaker.si/saker-a... Site was created using the downloads provided Regards Herb

The Saker blog is now frozen Tue Feb 28, 2023 23:55 | The Saker The Saker blog is now frozen Tue Feb 28, 2023 23:55 | The Saker

Dear friends As I have previously announced, we are now “freezing” the blog.? We are also making archives of the blog available for free download in various formats (see below).?

What do you make of the Russia and China Partnership? Tue Feb 28, 2023 16:26 | The Saker What do you make of the Russia and China Partnership? Tue Feb 28, 2023 16:26 | The Saker

by Mr. Allen for the Saker blog Over the last few years, we hear leaders from both Russia and China pronouncing that they have formed a relationship where there are

Moveable Feast Cafe 2023/02/27 ? Open Thread Mon Feb 27, 2023 19:00 | cafe-uploader Moveable Feast Cafe 2023/02/27 ? Open Thread Mon Feb 27, 2023 19:00 | cafe-uploader

2023/02/27 19:00:02Welcome to the ‘Moveable Feast Cafe’. The ‘Moveable Feast’ is an open thread where readers can post wide ranging observations, articles, rants, off topic and have animate discussions of

The stage is set for Hybrid World War III Mon Feb 27, 2023 15:50 | The Saker The stage is set for Hybrid World War III Mon Feb 27, 2023 15:50 | The Saker

Pepe Escobar for the Saker blog A powerful feeling rhythms your skin and drums up your soul as you?re immersed in a long walk under persistent snow flurries, pinpointed by The Saker >>

Interested in maladministration. Estd. 2005

RTEs Sarah McInerney ? Fianna Fail?supporter? Anthony RTEs Sarah McInerney ? Fianna Fail?supporter? Anthony

Joe Duffy is dishonest and untrustworthy Anthony Joe Duffy is dishonest and untrustworthy Anthony

Robert Watt complaint: Time for decision by SIPO Anthony Robert Watt complaint: Time for decision by SIPO Anthony

RTE in breach of its own editorial principles Anthony RTE in breach of its own editorial principles Anthony

Waiting for SIPO Anthony Waiting for SIPO Anthony Public Inquiry >>

Promoting Human Rights in IrelandHuman Rights in Ireland >>

In Episode 35 of the Sceptic: Andrew Doyle on Labour?s Grooming Gang Shame, Andrew Orlowski on the I... Fri May 09, 2025 07:00 | Richard Eldred In Episode 35 of the Sceptic: Andrew Doyle on Labour?s Grooming Gang Shame, Andrew Orlowski on the I... Fri May 09, 2025 07:00 | Richard Eldred

In Episode 35 of the Sceptic: Andrew Doyle on Labour?s grooming gang shame, Andrew Orlowski on the India-UK trade deal and Canada?s ignored Covid vaccine injuries.

The post In Episode 35 of the Sceptic: Andrew Doyle on Labour?s Grooming Gang Shame, Andrew Orlowski on the India-UK Trade Deal and Canada?s Ignored Covid Vaccine Injuries appeared first on The Daily Sceptic.

News Round-Up Fri May 09, 2025 00:56 | Richard Eldred News Round-Up Fri May 09, 2025 00:56 | Richard Eldred

A summary of the most interesting stories in the past 24 hours that challenge the prevailing orthodoxy about the ?climate emergency?, public health ?crises? and the supposed moral defects of Western civilisation.

The post News Round-Up appeared first on The Daily Sceptic.

The Sugar Tax Sums Up Our Descent into Technocratic Dystopia Thu May 08, 2025 19:00 | Dr David McGrogan The Sugar Tax Sums Up Our Descent into Technocratic Dystopia Thu May 08, 2025 19:00 | Dr David McGrogan

The sugar tax sums up Britain's descent into a technocratic dystopia, says Dr David McGrogan. While our Government does almost nothing well, it remains a world-leader in passive-aggressive, surreptitious nudging.

The post The Sugar Tax Sums Up Our Descent into Technocratic Dystopia appeared first on The Daily Sceptic.

UK ?Shafted? by US Trade Deal Thu May 08, 2025 17:44 | Will Jones UK ?Shafted? by US Trade Deal Thu May 08, 2025 17:44 | Will Jones

The US-UK trade deal announced today is a clear win for Trump, says Sam Ashworth-Hayes, leaving the UK worse off than in March and opening up UK markets in exchange only for reducing recently imposed tariffs.

The post UK “Shafted” by US Trade Deal appeared first on The Daily Sceptic.

Australia?s Liberal Party Only Has Itself to Blame for its Crushing Defeat by Labour Thu May 08, 2025 15:30 | Dr James Allan Australia?s Liberal Party Only Has Itself to Blame for its Crushing Defeat by Labour Thu May 08, 2025 15:30 | Dr James Allan

As in Canada, so in Australia, the crushing defeat of the conservative Liberal Party by Labour has been widely blamed on Trump. But in truth, Peter Dutton and his team only have themselves to blame, says Prof James Allan.

The post Australia’s Liberal Party Only Has Itself to Blame for its Crushing Defeat by Labour appeared first on The Daily Sceptic. Lockdown Skeptics >>

|

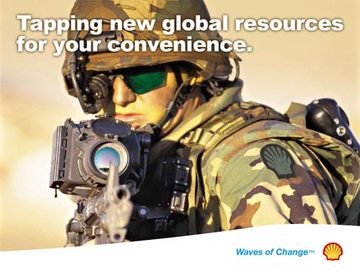

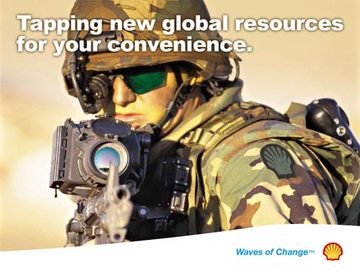

Reminder of Shell's Recent History before Rossport.

mayo |

environment |

other press mayo |

environment |

other press

Sunday January 01, 2006 20:56 Sunday January 01, 2006 20:56 by Niall Harnett - Shell to Sea / Rossport Solidarity Camp / Gluaiseacht by Niall Harnett - Shell to Sea / Rossport Solidarity Camp / Gluaiseacht

From the Ocean as Trash Pit to the land as Oil Slick.

This piece is a nice synopsis by Naomi Klein who summed up well Shell's recent history in her book 'No Logo'. I think it's worth reminding ourselves constantly why Shell are Hell.

Dempsey pumps for Shell. Since the 1950s, Shell Nigeria has extracted $30 billion worth of oil from the land of the Ogoni people, in the Niger Delta. Oil revenue makes up 80 per-cent of the Nigerian economy - $10 billion annually - and, of that, more than half comes from Shell. But not only have the Ogoni people been deprived of the profits from their rich natural resource, many still live with-out running water or electricity, and their land and water have been poisoned by open pipelines, oil spills and gas fires.

Under the leadership of the writer and Nobel Peace Prize nominee Ken Saro-Wiwa, the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP) campaigned for reform, and demanded compensation from Shell. In response, and in order to keep the oil profits flowing into the government's coffers, General Sani Abacha directed the Nigerian military to take aim at the Ogoni. They killed and tortured thousands. The Ogoni not only blamed Abacha for the attacks, they also accused Shell of treating the Nigerian military as a private police force, paying it to quash peaceful protest on Ogoni land, in addition to giving financial support and legitimacy to the Abacha regime.

Facing mounting protests within Nigeria, Shell withdrew from Ogoni land in 1993 - a move that only put further pressure on the military to remove the Ogoni threat. A leaked memo from the head of the Rivers State internal Security Force of the Nigerian Army was quite explicit: "Shell operations still impossible unless ruthless military operations are undertaken for smooth economic activities to commence. ... Recommendations: Wasting operations during MOSOP and other gatherings making constant military presence justifiable. Wasting targets cutting across communities and leadership cadres especially vocal individuals of various groups.

On May 10, 1994 - five days after the memo was written - Ken Saro-Wiwa said, "This is it. They [the Nigerian military] are going to arrest us all and execute us. All for Shell.” Twelve days later, he was arrested and tried for murder. Before receiving his sentence, Saro-Wiwa told the tribunal, "I and my colleagues are not the only ones on trial. Shell is here on trial. The company has, indeed, ducked this particular trial, but its day will surely come." Then, on November 10, 1995 - despite pressure from the international community, including the Canadian and Australian governments, and to a lesser extent the governments of Germany and France - the Nigerian military government executed Saro-Wiwa along with eight other Ogoni leaders who had protested against Shell. It became an international incident and, once again, people took their protests to their Shell stations, widely boycotting the company. In San Francisco Greenpeaceniks staged a re-enact- ment of Saro-Wiwa's murder, with the noose fastened around the towering Shell sign.

As Reclaim the Streets' John Jordan said of multinationals: "Inadvertently, they have helped us see the whole problem as one system." And here was that interconnected system in action: Shell, intent on sinking a monstrous oil platform off the coast of Britain, was simultaneously entangled in a human-rights debacle in Nigeria, in the same year that it laid off workers (despite earning huge profits), all so that it could pump gas into the cars of London - the very issue that had launched Reclaim the Streets. Because Ken Saro-Wiwa was a poet and playwright, his case was also claimed by the inter-national freedom-of-expression group, PEN. Writers, including the English playwright Harold Pinter and the Nobel Prize-winning novelist Nadine Gordimer, took up the cause of Saro-Wiwa's right to express his views against Shell, and turned his persecution into the highest-profile free- expression case since the government of Iran declared a fatwa against Salman Rushdie, offering a bounty on his head. In an article for The New York Times, Gordimer wrote that "to buy Nigeria's oil under the conditions that prevail is to buy oil in exchange for blood. Other people's blood; the exaction of the death penalty on Nigerians."

The convergence of social-justice, labor and environmental issues in the two Shell campaigns was not a fluke - it goes to the very heart of the emerging spirit of global activism. Ken Saro-Wiwa was killed for fighting to protect his environment, but an environment that encompassed more than the physical landscape that was being ravaged and despoiled by Shell's invasion of the delta. Shell's mistreatment of Ogoni land is both an environmental and a social issue, because natural-resource companies are notorious for lowering their standards when they drill and mine in third world counties. Shell’s opponents readily draw parallels between the company’s actions in Nigeria, its history of collaborating with the former apartheid governments in South Africa, its presence in the Timor Gap in Indonesian occupied East Timor and its violent clashes with the Nahau people of the Peruvian Amazon.

... (And then they came to Rossport. As the banner, held by the Rossport Five, at the front of the National Shell to sea rally in Dublin on Saturday October 1st, said ... 'DEMPSEY PUMPS FOR SHELL'. - Niall)

|

mayo |

environment |

other press

mayo |

environment |

other press

Sunday January 01, 2006 20:56

Sunday January 01, 2006 20:56 by Niall Harnett - Shell to Sea / Rossport Solidarity Camp / Gluaiseacht

by Niall Harnett - Shell to Sea / Rossport Solidarity Camp / Gluaiseacht

printable version

printable version

Digg this

Digg this del.icio.us

del.icio.us Furl

Furl Reddit

Reddit Technorati

Technorati Facebook

Facebook Gab

Gab Twitter

Twitter