North Korea Increases Aid to Russia, Mos... Tue Nov 19, 2024 12:29 | Marko Marjanovi? North Korea Increases Aid to Russia, Mos... Tue Nov 19, 2024 12:29 | Marko Marjanovi?

Trump Assembles a War Cabinet Sat Nov 16, 2024 10:29 | Marko Marjanovi? Trump Assembles a War Cabinet Sat Nov 16, 2024 10:29 | Marko Marjanovi?

Slavgrinder Ramps Up Into Overdrive Tue Nov 12, 2024 10:29 | Marko Marjanovi? Slavgrinder Ramps Up Into Overdrive Tue Nov 12, 2024 10:29 | Marko Marjanovi?

?Existential? Culling to Continue on Com... Mon Nov 11, 2024 10:28 | Marko Marjanovi? ?Existential? Culling to Continue on Com... Mon Nov 11, 2024 10:28 | Marko Marjanovi?

US to Deploy Military Contractors to Ukr... Sun Nov 10, 2024 02:37 | Field Empty US to Deploy Military Contractors to Ukr... Sun Nov 10, 2024 02:37 | Field Empty Anti-Empire >>

Indymedia Ireland is a volunteer-run non-commercial open publishing website for local and international news, opinion & analysis, press releases and events. Its main objective is to enable the public to participate in reporting and analysis of the news and other important events and aspects of our daily lives and thereby give a voice to people.

Trump hosts former head of Syrian Al-Qaeda Al-Jolani to the White House Tue Nov 11, 2025 22:01 | imc Trump hosts former head of Syrian Al-Qaeda Al-Jolani to the White House Tue Nov 11, 2025 22:01 | imc

Rip The Chicken Tree - 1800s - 2025 Tue Nov 04, 2025 03:40 | Mark Rip The Chicken Tree - 1800s - 2025 Tue Nov 04, 2025 03:40 | Mark

Study of 1.7 Million Children: Heart Damage Only Found in Covid-Vaxxed Kids Sat Nov 01, 2025 00:44 | imc Study of 1.7 Million Children: Heart Damage Only Found in Covid-Vaxxed Kids Sat Nov 01, 2025 00:44 | imc

The Golden Haro Fri Oct 31, 2025 12:39 | Paul Ryan The Golden Haro Fri Oct 31, 2025 12:39 | Paul Ryan

Top Scientists Confirm Covid Shots Cause Heart Attacks in Children Sun Oct 05, 2025 21:31 | imc Top Scientists Confirm Covid Shots Cause Heart Attacks in Children Sun Oct 05, 2025 21:31 | imc Human Rights in Ireland >>

Petrol Cars Now Cheaper to Run Than EVs After Tax Raid (Unless You Have a Driveway) Wed Dec 03, 2025 19:23 | Will Jones Petrol Cars Now Cheaper to Run Than EVs After Tax Raid (Unless You Have a Driveway) Wed Dec 03, 2025 19:23 | Will Jones

Rachel Reeves's new pay-per-mile tax will make petrol cars cheaper to run than electric vehicles unless drivers have a driveway and can charge them at home.

The post Petrol Cars Now Cheaper to Run Than EVs After Tax Raid (Unless You Have a Driveway) appeared first on The Daily Sceptic.

Covid Inquiry Costs Taxpayers ?100 Million More Than Thought Wed Dec 03, 2025 17:14 | Will Jones Covid Inquiry Costs Taxpayers ?100 Million More Than Thought Wed Dec 03, 2025 17:14 | Will Jones

The Covid Inquiry has cost taxpayers around ?100 million more than previously thought, according to official figures, once the colossal cost of the Government's responses to Baroness Hallett is included.

The post Covid Inquiry Costs Taxpayers ?100 Million More Than Thought appeared first on The Daily Sceptic.

Rachel Reeves Accused of Lying Over ?Chess Champion? Claims Wed Dec 03, 2025 15:30 | Will Jones Rachel Reeves Accused of Lying Over ?Chess Champion? Claims Wed Dec 03, 2025 15:30 | Will Jones

Rachel Reeves?has been accused of lying by exaggerating her chess achievements in a row over her claim she was "British girls' under-14 champion".

The post Rachel Reeves Accused of Lying Over “Chess Champion” Claims appeared first on The Daily Sceptic.

Labour Peer: Net Zero is Fantastical and Incoherent and Must Be Abandoned Wed Dec 03, 2025 13:25 | Maurice Glasman Labour Peer: Net Zero is Fantastical and Incoherent and Must Be Abandoned Wed Dec 03, 2025 13:25 | Maurice Glasman

Net Zero is fantastical and incoherent and must be abandoned for the sake of national security, leading Labour Peer Maurice Glasman has said. Read the full text of his 2025 Global Warming Policy Foundation annual lecture.

The post Labour Peer: Net Zero is Fantastical and Incoherent and Must Be Abandoned appeared first on The Daily Sceptic.

Jaguar Land Rover Designer Behind Woke Rebrand ?Escorted From Office? Wed Dec 03, 2025 11:01 | Will Jones Jaguar Land Rover Designer Behind Woke Rebrand ?Escorted From Office? Wed Dec 03, 2025 11:01 | Will Jones

The designer behind?Jaguar?s controversial woke rebrand?has reportedly been dismissed and "escorted from the office" just days after a new Chief Executive took over.

The post Jaguar Land Rover Designer Behind Woke Rebrand “Escorted From Office” appeared first on The Daily Sceptic. Lockdown Skeptics >>

Voltaire, international edition

Will intergovernmental institutions withstand the end of the "American Empire"?,... Sat Apr 05, 2025 07:15 | en Will intergovernmental institutions withstand the end of the "American Empire"?,... Sat Apr 05, 2025 07:15 | en

Voltaire, International Newsletter N?127 Sat Apr 05, 2025 06:38 | en Voltaire, International Newsletter N?127 Sat Apr 05, 2025 06:38 | en

Disintegration of Western democracy begins in France Sat Apr 05, 2025 06:00 | en Disintegration of Western democracy begins in France Sat Apr 05, 2025 06:00 | en

Voltaire, International Newsletter N?126 Fri Mar 28, 2025 11:39 | en Voltaire, International Newsletter N?126 Fri Mar 28, 2025 11:39 | en

The International Conference on Combating Anti-Semitism by Amichai Chikli and Na... Fri Mar 28, 2025 11:31 | en The International Conference on Combating Anti-Semitism by Amichai Chikli and Na... Fri Mar 28, 2025 11:31 | en Voltaire Network >>

|

On the Global Conjuncture, February 2014

international |

anti-capitalism |

opinion/analysis international |

anti-capitalism |

opinion/analysis

Thursday February 27, 2014 05:45 Thursday February 27, 2014 05:45 by Akbayan (Citizens Action Party - Philippines) by Akbayan (Citizens Action Party - Philippines)

The key feature of the global landscape is the continuing stagnation of the centers of the global economy, the United States and the European Union. The promise of sustained recovery from the financial implosion has eluded the United States for over three years now while most of Europe remains mired in very deep recession, with the notable exception of Germany.

Indefinite global stagnation

The stagnation is global since, unlike the case two years ago, China, India, and Brazil, which were then seen as the engines of global recovery, have begun to experience much lower growth rates. In the case of China, which, in 2012, became the world’s second biggest economy, the main problem was the failure to make the transition from an export-oriented economy to one driven mainly by the domestic market. The global picture, however, is not one of complete stagnation, since Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Africa continue to be marked by moderately high growth rates. However, these rates are expected to come down with the decline in demand for their exports from the so-called BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) countries, the continued stagnation in Europe and the US, and capital flight as the US Federal Reserve halts its expansionary monetary policy.

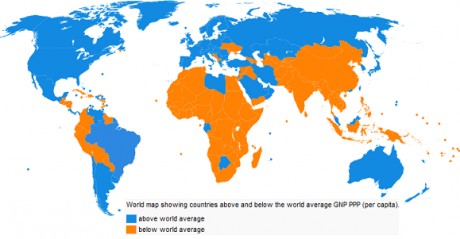

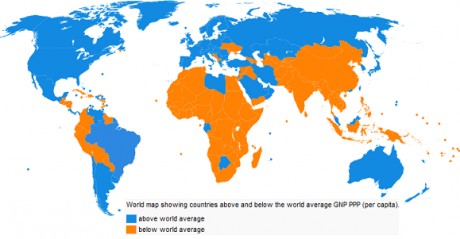

While the current crisis of global capitalism started as a financial crisis, it is now clear that it is rooted in the crisis of overproduction or overcapacity. This is the yawning gap between productive capacity and the limited capacity of consumers to absorb production owing to income inequality. With the integration of China into the capitalist world market over the last 30 years, the global economy has been loaded with tremendous overcapacity, even as the dynamics of finance capital, which has dominated and driven the accumulation process, has resulted in even greater inequality within and between nations. With the loss of significant new sources of global demand, apart from a massive redistribution of income both nationally and globally, the prospect, as many see it, is for years and years of stagnation. There is, of course, the prospect of massive military spending unleashed by a new arms race or a new Cold War, this time between China and the United States. While there are few indications as yet that this is the preferred exit strategy for global capital, it must not be discounted.

The Rise and Uncertain Future of the BRICS

An important feature of the last 15 years in particular has been the rise of the so-called BRICS. With relatively large populations and high growth rates, they increasingly saw themselves and began to move towards acting as a bloc to serve as a counterweight to the North even as they continued to be dependent on the North as a market for their goods and an absorber of their dollar earnings. While serving as a new pole in a multipolar world, the BRICs have not served as an alternative economic model. By and large, they have followed neoliberal domestic economic policies, though marked by a great degree of state intervention. They have also embraced neoliberal norms in their relations with the global economy. They have, for instance, increasingly been champions of free trade in the World Trade Organization, seeking new markets for their products with the decline in the importing capacity of their traditional markets in the North. The dynamism of the BRICs, however, has declined in recent years as they have been dragged down by the stagnation in the United States and Europe. Rather than leading to their dispersal, this will probably increase their efforts to act in concert to serve as one another’s market and in formulating common trade and investment approaches to both the North and the rest of the global South.

The US: From Comprehensive Global Dominance to the Pacific Pivot

In terms of geopolitics, the last few years have been marked by clumsy efforts on the part of the United States to retreat from the disastrous engagement in the Middle East to which the Bush II administration plunged it in its strive for overwhelming global military hegemony. While it has withdrawn from Iraq, the US has been unable to extricate itself from Syria, Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. It has been caught in the contradiction of seeking to maintain a regional political influence while at the same time radically limiting its military commitments as the American public no longer backs a substantial military engagement. In Libya, where the Obama administration intervened substantially, using Britain and France as fronts, the result has been disastrous, with the collapse of the Libyan state into anarchy that resulted in a blowback that saw Islamic militants kill the US ambassador and other US diplomatic personnel. In Afghanistan, Washington has not been able to make up its mind whether to withdraw or stay, even as the Taliban make impressive gains in their bid to regain state power. In Pakistan, Washington has resorted to illegal drone warfare waged by the Central Intelligence Agency to target militants, with many civilians dying as collateral damage, creating tremendous anti-US sentiment throughout the population.

The so-called Pacific Pivot of the Obama administration is a retreat from the comprehensive global dominance that was Washington’s strategy under the Bush II administration. While it is aimed at containing China, which the US now sees as the main threat to its global hegemony, it is at the same time a repositioning of US power to a more manageable stance of force projection in a familiar terrain where the Pentagon can play up the US advantages in naval and air power. The plan is to move 60 per cent of US naval forces to the Pacific, while tightening up alliances with South Korea, Japan, and the Philippines in order that these countries may not only serve as points for the projection or air power and as bases for the Navy but also so that they may engage their own military forces in the drive to contain China.

While there has been much hype about the US military repositioning, some analysts have pointed out that in an era when even the budget of the Pentagon is not exempt from deep cuts owing to pressures to radically reduce the budget deficit, Washington’s capacity to significantly upgrade its military capabilities is limited. Thus the focus is more on getting its allies to step up to the plate, and in this regard the military capabilities of Japan and South Korea are formidable. As Asia analyst John Feffer writes: “The Pacific pivot has been billed as a way to halt [the] drift [in US policy] and reinforce the U.S. position as a player in Asia. So far, however, this highly touted ‘rebalancing’ has essentially been a shell game, involving not a substantial build-up, but a shifting around of American forces in Asia…In an age of economic austerity and policy coordination with China, the Pacific pivot amounts to a complicated dance in which the United States steps backward as we propel our allies forward.”

The economic counterpart of the Pacific pivot is the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). A free trade scheme that would cover selected countries in the Western and Eastern Pacific, the TPP is a resurrection of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), but with a more explicit geopolitical intent, which is to isolate and contain China. The basic problem that the TPP faces is that the very countries it wants to draw in an economic alliance against China are also greatly dependent on China for trade and investment. The US itself is caught in a giant contradiction of being an economic rival to China at the same that it is China’s biggest debtor. China and the US are like two prisoners that can’t stand each other but are shackled with leg irons like Sidney Poitier and Tony Curtis. Moreover, disillusioned with the loss of jobs and markets owing to globalization, labor and other sectors of US society are wary about entering into another massive multilateral free trade deal like the World Trade Organization.

China’s Drive for Regional Hegemony

Washington’s pivot to the Pacific has been legitimized by China’s increasingly aggressive moves in the West Philippine Sea, aka South China Sea. China has destabilized the region with its unbelievable “Nine Dash Line” claim to over 95 per cent of the South China Sea, leaving other four other claimants, the Philippines, Vietnam, Brunei, and Malaysia, with just their 12-mile territorial waters. Where is China coming from?

There are three theories on the source of Chinese behavior. The first says it stems from insecurity. China’s increasingly aggressive rhetoric stems less from expansionist intent than from the insecurities brought about by high-speed capitalist growth followed by economic crisis. Long dependent for its legitimacy on delivering economic growth, domestic troubles related to the global financial crisis have left the Communist Party leadership groping for a new ideological justification, which it has found in virulent nationalism. The Xi Jen Ping leadership is particularly suitable for this role, according to some analysts, since it is said to be a “chickenhawk” administration led by people who have not been at war but love to play war, like George W. Bush and Dick Cheney in the US.

The second theory is related to the first. It is that China is poised to make major changes in its domestic political economy from which new winners and new losers will emerge owing to the exhaustion of the old export-led development model. An aggressive, nationalist stance of pushing territorial claims in the West Philippine Sea and the Western Pacific, near Japan and Korea, would, in this view, would be a way of containing centrifugal forces as the Communist Party carries out a comprehensive program of reform.

The third theory, the conventional view, is that China’s moves reflect the cold calculation of a confidently rising power. It aims to stake a monopoly over the fishing and energy resources of the West Philippine Sea in its bid to become a regional and later, a global hegemon. But whatever the source of its behavior, Beijing’s moves have alarmed its neighbors, and may be forcing them into the hands of the United States by allowing the latter to portray itself as a military savior or “balancer.”

Volatile Brew

The US-China sparring is volatile enough, but there is a third source of destabilization in the region: Japan. Right-wing elements there, including the current Prime Minister Shinzuo Abe, have taken advantage of China’s moves in the West Philippine Sea and Japan’s dispute with Beijing over the deserted Senkaku Islands to push for the abolition of Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution, which prohibits war as an instrument of foreign policy and prevents Japan from having an army. Their aim is to have a foreign and military policy more independent from the US, which has managed Tokyo’s external security affairs ever since Japan’s defeat during the Second World War.

Many of Japan’s neighbors are convinced that a Japan more independent from the US will develop nuclear weapons, and they fear the prospect of a nuclear-armed Japan that has shed its post-war pacifism and not yet carried out the national soul searching that in Germany embedded responsibility for the atrocities of Nazi Germany in the national consciousness.

In any event, the Western Pacific extending from the West Philippine Sea to Japan has become one of the world’s three flashpoints, the two others being Iran and Israel-Palestine. China’s aggressive territorial claims, the US’s Pivot to Asia, and Japan’s opportunistic moves add up to a volatile brew.

In the middle of this powderkeg is the Philippines which, with the acquiescence of the Aquino administration, is being turned into a frontline state by the United States. While the Philippines has rightfully elevated its dispute with China to the United Nations Arbitral Tribunal on the Law of the Seas, the main policy thrust of the administration in the Asia Pacific has been to invite a more active military presence of the United States to contain China. Ostensibly aimed at promoting a solution to the conflicting territorial claims of China and the Philippines in the West Philippine Sea, the embrace of the US is likely, on the contrary, to marginalize such a process by transforming the dynamics of the situation from a territorial dispute into simply nother dimension of a superpower conflict.

Many observers note that the Asia Pacific military-political situation is becoming like that of Europe at the end of the 19th century, with the emergence of a similar configuration of balance of power politics. It is a useful reminder that while that fragile balancing might have worked for a time, it eventually ended up in the conflagration that was the First World War. None of the key players may want war. On this there is consensus. But neither did any of the Great Powers during the First World War. The problem is that in a situation of fierce rivalry among powers that hate one another, an incident may trigger an uncontrollable chain of events that may result in a regional war, or worse.

The State of Global Resistance

From 2008 to 2012, two people’s movements emerged on the global stage, the Occupy Movement in the North and the Arab Spring in the Middle East.

The Occupy Wall Street Movement in the US and its counterparts in Europe were a response to the financial collapse and the consequent bailout of the banks even as people suffered high rates of unemployment. Its base was the youth in the North, who were hit with rates of unemployment that came to 40 to 50 per cent in some countries. Occupy was largely a spontaneous movement, and it spread very quickly. It faded equally quickly in 2012, dealt a fatal blow by the inability of its leaders to give it a more solid organization. In fact, Occupy distrusted and discouraged the emergence of leaders as well as efforts to give the movement a more solid theoretical and ideological grounding beyond spontaneous activism against finance capital and the state.

In many countries in Europe, there was great expectation that the economic crisis would result in leftwing parties coming to power. In fact, the opposite was true, with conservative governments coming to power or staying in power in Britain, Greece, Spain, and Germany. France was the one major country in Europe where Social Democrats came to power, with Francois Hollande winning the election for the presidency in 2013. Hollande’s policies, however, turned to the right later in the year, causing his deep plunge in public opinion polls.

In the United States, Obama won the presidency in 2008 and was reelected in 2012. Except for health care reform, however, other liberal initiatives he promised were stymied by a Republican majority in the House of Representatives, which he conciliated rather than challenged. In foreign policy, as we have already shown, Obama’s moves quickly doused any hope that his presidency would mark a major change in Washington’s imperial approach to the world.

When the Arab Spring broke on the global scene in 2011, there were expectations that democratic rule would come to the Middle East. In 2014, the only country to have made some sort of democratic transition is Libya. Elsewhere, expectations were dashed. In Syria, authoritarian resistance and foreign intervention have so far throttled attempts at a democratic breakthrough. In Egypt, a military-led counterrevolution destroyed a fragile, democratically-elected government. In Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states, entrenched feudal elites managed to defuse popular pressures for democratization through a combination of iron-fist measures, playing the anti-Shiite, anti-Iran card, or pushing welfare reforms meant to pacify unemployed youth. In Bahrain, Saudi intervention smashed the democracy movement, at least for the time being. So far, the only clear winners in the Middle East have been radical Islamist movements, like Al Qaeda and the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which have supplanted secular pro-democracy movements as the leading force in the opposition.

There is, however, one instance, when progressive forces registered a victory, and this was the global outcry that greeted and stopped Obama’s push to bomb Syria in August 2014. Akbayan was one of these voices, and we should be proud that we fulfilled our internationalist duty during that decisive moment.

https://akbayan.org.ph/news

GDP per Capita

Human Development Index

|

international |

anti-capitalism |

opinion/analysis

international |

anti-capitalism |

opinion/analysis

Thursday February 27, 2014 05:45

Thursday February 27, 2014 05:45 by Akbayan (Citizens Action Party - Philippines)

by Akbayan (Citizens Action Party - Philippines)

printable version

printable version

Digg this

Digg this del.icio.us

del.icio.us Furl

Furl Reddit

Reddit Technorati

Technorati Facebook

Facebook Gab

Gab Twitter

Twitter